In March, Pires showed up at the immigration office with paperwork listing all her check-ins over the past eight years. This time, instead of receiving another compliance report, she was immediately handcuffed and detained.

“The government failed her,” attorney Jim Merklinger said. “They allowed this to happen.”

It sounded like freedom, like a world of possibility beyond the orphanage walls.

Maria Pires was getting adopted. At 11 years old, she saw herself escaping the chaos and violence of the Sao Paulo orphanage, where she’d been sexually assaulted by a staff member. She saw herself leaving Brazil for America, trading abandonment for belonging.

A single man in his 40s, Floyd Sykes III, came to Sao Paulo to meet her. He signed some paperwork and brought Maria home.

She arrived in the suburbs of Baltimore in the summer of 1989, a little girl with a tousle of dark hair, a nervous smile and barely a dozen words of English. The sprawling subdivision looked idyllic, with rows of modest brick townhouses and a yard where she could play soccer.

She was, she believed, officially an American.

But what happened in that house would come to haunt her, marking the start of a long descent into violence, crime and mental illness.

“My father — my adopted father — he was supposed to save me,” Pires said. Instead, he tortured and sexually abused her.

After nearly three years of abuse, Sykes was arrested. The state placed Pires in foster care.

By then, she was consumed with fury. In the worst years, she beat a teenager at a roller rink, leaving him in a coma. She attacked a prison guard and stabbed her cellmate with a sharpened toothbrush.

In prison, she discovered that no one had ever bothered to complete her immigration paperwork. Not Sykes. Not Maryland social service agencies.

That oversight would leave her without a country. She wasn’t American, it turned out, and she’d lost her Brazilian citizenship when she was adopted by Sykes, who died several years ago. But immigration officials, including those under President Donald Trump’s first administration, let her stay in the country.

After her release from prison in 2017, Pires stayed out of trouble and sought help to control her anger. She checked in once a year with Immigration and Customs Enforcement and paid for an annual work permit.

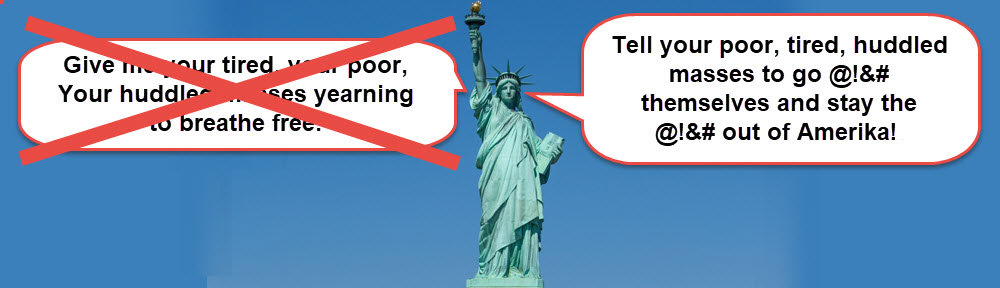

But in the second Trump administration — with its promise of mass deportations, a slew of executive orders and a crackdown targeting those the president deemed “the worst of the worst” — everything changed. Trump’s unyielding approach to immigration enforcement has swept up tens of thousands of immigrants, including many like Pires who came to the U.S. as children and know little, if any, life outside America. They have been apprehended during ICE raids, on college campuses, or elsewhere in their communities, and their detentions often draw the loudest backlash.

In Pires’ case, she was detained during a routine check-in, sent to one immigration jail after another, and ultimately deported to a land she barely remembers. The Associated Press conducted hours of interviews with Pires and people who know her and reviewed Maryland court records, internal ICE communications, and adoption and immigration paperwork to tell her story.

U.S. immigration officials say Pires is a dangerous serial criminal who’s no longer welcome in the country. Her case, they say, is cut and dried.

Pires, now 47, doesn’t deny her criminal past.

But little about her story is straightforward.

A new chapter of childhood, marked by abuse

Pires has no clear memories from before she entered the orphanage. All she knows is that her mother spent time in a mental institution.

The organization that facilitated her adoption was later investigated by Brazilian authorities over allegations it charged exorbitant fees and used videos to market available children, according to a Sao Paulo newspaper. Organization leaders denied wrongdoing.

Pires remembers a crew filming a TV commercial. She believes that’s how Sykes found her.

In his custody, the abuse escalated over time. When Sykes went to work, he sometimes left her locked in a room, chained to a radiator with only a bucket as a toilet. He gave her beer and overpowered her when she fought back. She started cutting herself.

Sykes ordered her to keep quiet, but she spoke almost no English then anyway. On one occasion, he forced a battery into her ear as punishment, causing permanent hearing loss.

In September 1992, someone alerted authorities. Sykes was arrested. Child welfare officials took custody of Maria, then 14.

Maryland Department of Human Services spokesperson Lilly Price said the agency couldn’t comment on specific cases because of confidentiality laws but noted in a statement that adoptive parents are responsible for applying for U.S. citizenship for children adopted from other countries.

Court documents show Sykes admitted sexually assaulting Maria multiple times but he claimed the assaults stopped in June 1990.

He was later convicted of child abuse. Though he had no prior criminal record, court officials acknowledged a history of similar behavior, records show.

Between credit for time served and a suspended prison sentence, Sykes spent about two months in jail.

Sykes’ younger sister Leslie Parrish said she’s often wondered what happened to Maria.

“He ruined her life,” she said, weeping. “There’s a special place in hell for people like that.”

Parrish said she wanted to believe her brother had good intentions; he seemed committed to becoming a father and joined a social group for adoptive parents of foreign kids. She even accompanied him to Brazil.

But in hindsight, she sees it differently. She believes sinister motives lurked “in the back of his sick mind.”

At family gatherings, Maria didn’t show obvious signs of distress, though the language barrier made communication difficult. Other behavior was explained away as the result of her troubled childhood in the orphanage, Parrish said.

“But behind closed doors, I don’t know what happened.”

Years in prison and an eventual release

Pires’ teenage years were hard. She drank too much and got kicked out of school for fighting. She ran away from foster homes, including places where people cared for her deeply.

“If ever there was a child who was cheated out of life, it was Maria,” one foster mother wrote in later court filings. “She is a beautiful person, but she has had a hard life for someone so young.”

She struggled to provide for herself, sometimes ending up homeless. “My trauma was real bad,” she said. “I was on my own.”

At 18, she pleaded guilty to aggravated assault for the roller rink attack. She served two years in prison, where she finally learned basic reading and writing skills. It was then that authorities — and Pires herself — discovered she wasn’t a U.S. citizen.

Her criminal record meant it would be extremely difficult to gain citizenship. Suddenly, she faced deportation.

Pires said she hadn’t realized the potential consequences when accepting her plea deal.

“If l had any idea that I could be deported because of this, I would not have agreed to it,” she wrote, according to court records. “Going to jail was one thing, but I will lose everything if I am deported back to Brazil.”

A team of volunteer lawyers and advocates argued she shouldn’t be punished for something beyond her control.

“Maria has absolutely no one and nothing in Brazil. She would be completely lost there,” an attorney wrote in a 1999 letter to immigration officials.

Ultimately, the American judicial system agreed: Pires would be allowed to remain in the United States if she checked in annually with ICE, a fairly common process until Trump’s second term.

“How’s your mental?”

Pires didn’t immediately take advantage of her second chance.

She was arrested for cocaine distribution in 2004 and for check fraud in 2007. While incarcerated, she picked up charges for stabbing her cellmate in the eye, burning an inmate with a flat iron and throwing hot water on a correctional officer. Her sentence was extended.

Pires said she spent several years in solitary confinement, exacerbating her mental health challenges.

Her release in 2017 marked a new beginning. Through therapy and other support services, she learned to manage her anger and stay out of trouble. She gave up drinking. She started working long days in construction. She checked in every year with immigration agents.

But in 2023, work dried up and she fell behind on rent. She felt her mental health slipping. She applied for a women’s transitional housing program in Baltimore.

Pires thrived there. With no high school diploma and only second-grade reading skills, she qualified for a state-run job training course to polish and refinish floors. Photos show her smiling broadly in a blue graduation gown.

Friends say Pires may have a tough exterior, but she’s known for thinking of others first. She often greets people with a cheerful question: “How’s your mental?” It’s her way of acknowledging that everyone carries some sort of burden.

“This is a person who just yearns for family,” said Britney Jones, Pires’ former roommate. “She handles things with so much forgiveness and grace.”

The two were living together when Pires went to downtown Baltimore on March 6 for her annual immigration check-in. She never returned.

A crackdown on “the worst of the worst”

When President Donald Trump campaigned for a second term, he doubled down on promises to carry out mass deportations. Within hours of taking office, he signed a series of executive orders, targeting what he called “the worst of the worst” — murderers, rapists, gang members. The goal, officials have said, is 1 million deportations a year.

In March, Pires showed up at the immigration office with paperwork listing all her check-ins over the past eight years. This time, instead of receiving another compliance report, she was immediately handcuffed and detained.

“The government failed her,” attorney Jim Merklinger said. “They allowed this to happen.”

Given that she was adopted into the country as a child, she shouldn’t be punished for something that was out of her hands from the start, he said.

Her March arrest sparked a journey across America’s immigration detention system. From Baltimore, she was sent to New Jersey and Louisiana before landing at Eloy Detention Center in Arizona.

She tried to stay positive. Although Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric made her nervous, Pires reminded herself that the system granted her leniency in the past. She told her friends back home not to worry.

A deportation priority

On June 2, in an email exchange obtained by AP, an ICE agent asked to have Pires prioritized for a deportation flight to Brazil leaving in four days.

“I would like to keep her as low profile as possible,” the agent wrote.

Her lawyer tried to stop the deportation, calling Maryland politicians, ICE officials and Brazilian diplomats.

“This is a woman who followed all the rules,” Merklinger said. “This should not be happening.”

He received terrified calls from Pires, who was suddenly transferred to a detention facility near Alexandria, Louisiana, a common waypoint for deportation flights.

Finally, Pires said, she was handcuffed, shackled, put on a bus with dozens of other detainees, driven to the Alexandria airport and loaded onto an airplane. There was a large group of Brazilians on the flight, which was a relief, though she spoke hardly any Portuguese after so many years in the U.S.

“I was just praying to God,” she said. “Maybe this is his plan.”

After two stops to drop off other deportees, they arrived in the Brazilian port city of Fortaleza.

Starting from scratch back in Brazil

Brazilian authorities later took Pires to a women’s shelter in an inland city in the eastern part of the country.

She has spent months there trying to get Brazilian identification documents. She began relearning Portuguese — listening to conversations around her and watching TV.

Most of her belongings are in a Baltimore storage unit, including DJ equipment and a tripod she used for recording videos — two of her passions.

In Brazil, she has almost nothing. She depends on the shelter for necessities such as soap and toothpaste. But she maintains a degree of hope.

“I’ve survived all these years,” Pires said. “I can survive again.”

She can’t stop thinking about her birth family. Years ago, she got a tattoo of her mother’s middle name. Now more than ever, she wants to know where she came from. “I still have that hole in my heart,” she said.

Above all, she hopes to return to America. Her attorney recently filed an application for citizenship. But federal officials say that’s not happening.

“She was an enforcement priority because of her serial criminal record,” Department of Homeland Security Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in an email. “Criminals are not welcome in the U.S.”

Every morning, Pires wakes up and keeps trying to build a new life. She’s applied for Brazilian work authorization, but getting a job will probably be difficult until her Portuguese improves. She’s been researching language classes and using her limited vocabulary to communicate with other shelter residents.

In moments of optimism, she imagines herself working as a translator, earning a decent salary and renting a nice apartment.

She wonders if God’s plan will ever become clear.